“How can I celebrate him? I took it on myself to do everything that he should have done in this world, I tried to carry that a little bit myself. That’s when I took on his name as my middle name.”

— Geoffrey Owen Miller, Multidisciplinary Artist

Monday, September 30th, 2013

On the Road: Journal Entry No. 5

Santa Fe to White Sands, New Mexico

Although the majority of Land Art Road Trip participants started the journey together in Salt Lake City, there were a good number of artists who joined later on in the trip. I’m not sure exactly how that difference may have altered their experiences, but I did notice that forming the connections that majority of us had quickly established may have been a bit more difficult for those who came later. This is understandable considering most already felt a bond with someone after camping without any amenities in the middle of nowhere. That experience is very different from when you are just driving out from a lush airport to meet those who had participated in the aforementioned activity. Of course, the newer members eventually settled in to the Gerson Zevi family. If you could hang in a fly filled van for a while without complaining, you were golden. Yet some made more memorable entrances into the group then the others; one of those instances was the night that Geoffrey Owen Miller met the group.

Geoffrey joined us at the Apache National Forest in New Mexico, arriving late due to his full-time job out in New York City. Calm and collected, he initially made a quiet entry into the group until the day turned to dusk. For reasons unknown, Geoffrey made the bold decision to camp out on the roof of one of the two trailers. This might not seem odd knowing that some artists slept beside, inside, or on top of some of the Land Art works we had visited, but this was different. Despite warnings that he might “freeze his ass off,” Geoffrey stuck it out. Entranced by the stars and wooded surroundings he seemed to care less about the frigid temperatures. That was the interesting thing about Geoffrey; if something seemed to interest him, he dove right into it.

In a way that is unique to Geoffrey, his passion is apparent as soon as you first speak to him. He always seems to have an encyclopedia of information stored in the event that there is a perfect time to share it. That may come from being both an avid learner and also a professional teacher. His knowledge of art comes from a wealth experiences and a deep interest in educating himself in the field. The opportunity to explore the South West, an area he had already been a bit familiarized with both from growing up in New Mexico and reading on the artists’ work we were traveling too, meant the world to him. Despite his commitments in New York, he made the time to get out here and the group was incredibly happy that he did. With a smile always on his face, Geoffrey exudes a certain kind of positivity that makes you believe that everything is perfect and nothing can go wrong. Yet, after sitting down and speaking to him about his work and the experiences that have inspired it I learned that the person he presents to the world is so much braver than his seemingly confident exterior suggests.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Q + A W/ GEOFFREY OWEN MILLER

MULTIDISCIPLINARY ARTIST - NEW YORK, NY

Sarah Mendelsohn: Well, I saw on your CV that you have been doing this for a really long time.

Geoffrey Miller: (laughs) I’m the oldest person in the group. Mentally, maybe not.

SM: You went to college for art, right?

GM: Basically, I had gone to college not knowing what I wanted to do and I ended up getting the chance to live in Spain. So, I went there, made some friends and when I came back I changed my major to Spanish so I could go back on purpose. I studied Spanish, finished a Spanish degree and was going to graduate and it was right about then that I found out that my brother ran away from home and committed suicide. Then I basically just stayed in school so that I could do a second major. I did illustration, painting, graphic design- everything that had to do with visual communication. In my mind, if I was going to take this seriously I wanted to really explore the physical side of it as much as possible; the undergrad school I was in was excellent at this aspect. Then I could go to grad school and think about the history and the context. So that’s what I tried to do.

SM: So, after your brother passed away, is that what you did to express yourself, to deal with what happened?

GM: Yeah. I made a bunch of really terrible pieces of work that were sort of supposed to deal with that issue. It’s cathartic, it makes you feel better to have something that expresses that. I was tasked with designing his grave stone. That was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. For a job you want to get right, that was just one of those jobs where you don’t want to think about how you didn’t do a good job.

“That was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. For a job you want to get right, that was just one of those jobs where you don’t want to think about how you didn’t do a good job.”

SM: Is that something you decided you wanted to do or were you asked to do it?

GM: Since I was the creative one in the family, they asked me if I wanted to do it and I felt like it fell to me. That was my task. Being his brother, I was the closest one to him in the family. We ended up doing something that I thought was really brilliant in a way. We just took his name, we scanned it from one of his signatures and they lazer cut it into the stone. When you see the stone, you just see his signature and it has so much of his character. He was such a great kid, so smart and funny. That personality comes through.

SM: That’s very sweet that you did that for him. So you decided to make that your major in school after all of that happened?

GM: Yeah, I have wrestled with suicide myself and that’s why it was always surprising that he was the one that went through with it. We always thought that he was the one who had his shit together. I thought I could die for whatever reasons or I could do something meaningful with this time. Also, how can I celebrate him? I took it on myself to do everything that he should have done in this world, I tried to carry that a little bit myself. That’s when I took on his name as my middle name. When I was born, I had that name. I had two middle names because my parents liked those names and when he was born he took that name. So, I took that name back on, thinking of him being a part of me now.

SM: So after you received your art degree and left college, what did you do?

GM: When I finished undergrad in California, I knew that I wanted to live on the East coast. Having lived in Spain, I understood that you receive so much education just from being somewhere else. The little things that other people do, the decisions they make and the way they see the world is so informative; I knew that I needed to live on the opposite side of the country to see how people thought about things there. I ended up in upstate New York because of a girlfriend at the time, living in a small town north of the city and just working odd jobs. I installed drywall one day, transported materials the next day, whatever I happened to get. They always talk about freelance as being this happy go lucky job, but it’s just stressful and you never know when you’re going to get paid.

“Having lived in Spain, I understood that you receive so much education just from being somewhere else. The little things that other people do, the decisions they make and the way they see the world is so informative; I knew that I needed to live on the opposite side of the country to see how people thought about things there.”

Around that time, I started substitute teaching at the elementary, middle school and high school over there. One day it would be elementary art and the next day it was middle school PE. I was all over the place. It was really interesting because you get a sense of all the grade groups. You go from sweet, but totally clueless elementary school kids to out of control middle schoolers to high schoolers who are starting to understand the world a little bit, but still don’t quite understand what they’re doing for their own benefit. It was really interesting. Through that, a Spanish teaching job opened up. The Spanish teacher got pregnant and they couldn’t find a substitute that they liked better than me, so they ended up hiring me full time for that semester. I ended up teaching three different classes, all sorts of kids, everything from freshmen with disabilities to seniors that were getting college credit. They wanted me to keep going, but that spring I got accepted to graduate school and I started to get back into art.

l did that and was in Massachusetts for three years. When I finished, I ended up back in the city, freelancing and working at a Turkish restaurant. You know, I’m not very good at selling myself. I was never like, “Oh yeah, I can do anything!” I was more like, “Okay, yeah, I think I can do it.” But it fed me for a few months and I had a job, where many of my peers who had got out of school at the same time were having difficulty finding them. It was a shitty job, but one none the less.

SM: Yeah, you seemed to graduate at the wrong time. The start of the recession was tough.

GM: Yeah, it didn’t last long, though. I soon began working for an artist as an assistant. That was really educational. I don’t know if I want to say who he was because I just have bad things to say about him. The thing is, you realize what desperation does and you also realize that New York really functions off of people using other people. I said I’d work for him for five bucks an hour.

“The thing is, you realize what desperation does and you also realize that New York really functions off of people using other people.”

SM: Oh my god, but you can’t live in New York on that much.

GM: No, but it was experience and I was trying to get something going. The truth is when you’re working really hard for somebody, you can get other jobs really easily. So that did get me other jobs at wood shops and other things like that, but I think badly of it because I did so much hard work for him and he was so ungrateful in the end. It soured that relationship. At the time, I was proud to have helped him on his projects.

SM: Did you learn a lot from that experience regardless?

GM: I learned about the personalities that operate in the art world and how they get as far as they do. There’s a lot of things about him that I didn’t like, but he had a very strong personality. He was really good at making people feel appreciated when he wanted something and I saw that first hand. It’s not something I learned from as if I could do that, because it feels very antithetical to my character, but I got a bit more of an understanding on how that functions.

SM: What happened after you fell out of that?

GM: It got worse and worse over a period of years and then during that time I started working for another artist that the first artist actually mocked. This artist made his work out of Legos and he took it very seriously. It’s kind of ridiculous.

SM: That sounds really cool, though.

GM: Oh, it was amazing and I learned a lot from that job. I learned organization. I learned how to deal with people and having managerial skills. This guy came from designing software for the Lehman brothers and started this small business designing these large scale Lego sculptures. He did everything from inventory to the building to the sculptural process and the iteration of long term planning and time sheets; he gravitated towards computer designing later on when his work became more complex. It was a fantastic experience. I left it to teach again and I’m kind of sad about it. It was one of the most flexible jobs I’ve ever had. He was very understanding about taking time off for other things.

SM: So now you’re balancing teaching and doing your art work.

GM: Yes, now I’m working two part time jobs. The thing that’s difficult about teaching is that it’s hard to put boundaries on your time because you could always do more and spend more time on each of the children. They deserve as much as you can give, especially the ones that are receptive. Some you kind of clash with, but the sweet ones, especially the younger kids, you want to give them all you can so that they can be as good as they can be.

“The thing that’s difficult about teaching is that it’s hard to put boundaries on your time because you could always do more and spend more time on each of the children. They deserve as much as you can give, especially the ones that are receptive. You want to give them all you can so that they can be as good as they can be.”

SM: So now you’re balancing teaching and doing your art work.

GM: Yes, now I’m working two part time jobs. The thing that’s difficult about teaching is that it’s hard to put boundaries on your time because you could always do more and spend more time on each of the children. They deserve as much as you can give, especially the ones that are receptive. Some you kind of clash with, but the sweet ones, especially the younger kids, you want to give them all you can so that they can be as good as they can be.

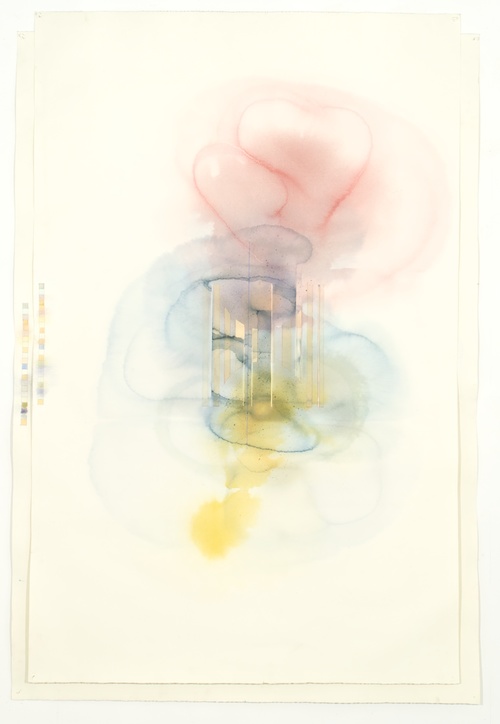

SM: I want to talk about your work. You’re a painter. That is your medium, right?

GM: I’ve started doing sculpture, actually. I haven’t put it online because I’m not sure of how to present it yet. In the last year, I’ve done a lot of sculpture. I’ve done box-like structures out of wood and I’ve gone back into that, using different forms of chemistry to play with the age of objects. It’s something that water colors have made me think about, this idea of the accumulation of time. It’s very appropriate on this Land Art trip because you drive through New Mexico and Arizona and you see all the strata. That’s something that’s sort of burned into my head: the way that you’re driving through time. There’s history in the land and the way that it sort of builds into these physical sculptures. Erosion and accumulation is what creates present day land.

SM: Why did you decide to make the transition from 2D to 3D?

GM: Partially, it’s nervousness about trying to understand the medium I was working in. I thought I was an oil painter and that’s because oil paint is a fantastic medium. It’s super flexible and there’s this great tradition. For me to understand something, sometimes I need to look at something else in order to compare it. Often when I’m working on one project I get stuck and I need to do something else. I don’t know why I started playing with 3D things, but one thing kind of leads to another and sometimes it gets totally excessive and I’m playing with something that’s just totally random. Like, I was growing crystals this summer. I don’t even remember how I got there, but I had a lot of fun doing it.

SM: Are you going to present that work? Those sculptures?

GM: Yes, but sculpture is harder to place and deal with. So, most of the time when people come to look at my work, they’ll look at it and they’ll like it, but it’s so much easier for people to look at and accept 2D work. It’s something I’m going to continue doing until it gets to a point where I think I can’t. I’ve been playing with plaster, wood and found objects a little bit and also casting. I taught printmaking and the idea of multiples, the way that they’re similar, but different and so casting is another form of that that’s just natural. I also worked for Allan McCollum for a little bit and he did the plaster surrogates. I think he’s really intelligent in the way that he mines culture and finds these interesting things; that sort of thing of how one thing bridges to another has always been interesting to me. When I first experienced his work in undergrad, I didn’t like it. When I came to understand it, it became some of my favorite work. To get to work for him was such a treat; he’s such a sweet man.

SM: That’s really cool. So sculpture is what you’re currently working on?

GM: No, that’s the thing- I jump from thing to thing. I was in a residency this summer in France and I did some watercolors and washes that will go with these large scale paintings that sort of use the docs I’ve been using, that language and create these forms that are like crystals. I had this experience with this Michael Heizer piece at the Dia Foundation, Beacon and it really resounded with me in a way that I was able to translate into this very colorful, pop-like painting. I think it will receive a lot of attention. At the same time, I’m working on implementing this system with these modules and this idea of multi-panel paintings that aren’t painted with a plan previously. Sounds like a rhyme, ha. They’re assembled later so it’s more about chance. It’s the accumulation of error to a point where it comes together into something that unites. It goes in line with the way life functions. They look sort of like cells in some ways. At the very beginning, they were based on eyes with the idea that eyes are the window into a person’s mind. I’m thinking about making them into these quilts and I’m really excited about it. It’s just about finding the time to make a bunch of bad ones so some good ones come out.

SM: So you seem to be inspired by a variety of things. I heard you once say something about video games giving you an artistic idea.

GM: Yeah, all over the place. I worked with this guy, Shane Campbell, on developing a video game. He also influenced me to work on these large scale narrative paintings of Moby Dick because he was also working on narrative paintings. He’s an artist I really respect and I’ve worked with him since I was in undergrad.

SM: You’ve done a lot of work with other artists and also by yourself. Do you like collaborating?

GM: I do with the right artists. When I work on projects with others, I tend to struggle in the beginning. Even with the Lego jobs, after I had done three or four of them I had no idea of how I was going to get to the end. I was just overwhelmed. Somehow, you get to a point where all a sudden it just starts clicking and it’s this amazing sensation of creating something.

SM: Do you plan to ever pursue your career as an artist full time and leave teaching behind?

GM: I’m just trying to buy myself more time to work. You live such a short amount of time. I just had a great conversation with this fabulous artist named Oliver Herring and he was desperate to not waste time on frivolous things. We really don’t have that much time to work. The difficult thing for me is that you learn so much from every event that happens in your life and then it gets integrated into your being. It’s like Ernest Hemingway could only write his novels because he was living life as Ernest Hemingway. So, at what point do you say no to things in order to work, to be a Producer? At what point do you say yes and grow and learn from something?

“The difficult thing for me is that you learn so much from every event that happens in your life and then it gets integrated into your being. It’s like Ernest Hemingway could only write his novels because he was living life as Ernest Hemingway. So, at what point do you say no to things in order to work, to be a Producer? At what point do you say yes and grow and learn from something?”

SM: So you must really like residencies then.

GM: They’re new to me, but yeah. The last one was fantastic and my ideal situation is to surround myself with people who feel that pressure of needing to do something, but at the same time want interaction. Some people aren’t accepting of that. If you’re not totally present with them because you’re distracted by something they don’t have the same understanding sometimes. I’ve lost friends that way, which is really sad.

SM: What have you taken from this opportunity thus far?

GM: The land art works that I’ve gotten to see, you don’t really understand until you get to see them. That benefits me as an artist to see them and also as a teacher to be able to talk about them. It’s entirely different experience than to read about it. Also, having conversations with the people here is very fruitful. I’ve started to have more deep conversations with people about the world and how they personally operate and what they’re hoping to accomplish. To talk to other people in your professional stage and to hear about what they’re doing is priceless in a lot of ways. There’s no other source; I mean I guess you could read about it in interviews like this, but they’re often edited for certain reasons.

SM: Your words won’t be altered, by the way.

GM: It’s like you want to be heard by people. You want to be paid attention to, but at the same time there’s something so comforting about anonymity. I don’t know. Like I said, I’m just trying to figure out how to buy time to make work. Some people feel like you can just get a normal job and do it on your own and that’s enough, but there’s a social component that’s important to me where I want enough of myself that’s public so I can attract or be attracted to people with similar ideas and then focus on the work. I’m not an artist that tweets or Instagrams everything. I use those things very infrequently, but I do want to find other creatives. I think those mediums are great for interacting with people of like minds, and I think that’s one of the beauties of this world.

“It’s like you want to be heard by people. You want to be paid attention to, but at the same time there’s something so comforting about anonymity.”

SM: That’s a hard thing to transition into, though. You’re old enough where ten years ago, people didn’t Facebook everything. That’s an entirely new medium to every industry, including art. Today, people equate having a ton of Facebook likes to being established. You’re old enough where you were pursuing a career in the art industry where that didn’t exist yet. Has social media becoming so prominent in everything that it’s become difficult for you at all?

GM: I’m not a fish in water with it where it just feels totally natural and it automatically feeds me. If I get a like or two, I think, “Oh, that’s great.” That’s the thing about being an artist; you have to do everything at some point. The famous people, if they know what they’re doing, they’re in control of everything. That’s part of our world. Some people can make it a thing to not be about the internet, but I’m certainly not mysterious enough to do that.

SM: You are a bit mysterious, though. You have this cool, easy going vibe about you. Then I sat down and talked to you and you laid down some real shit. Another question unrelated to that though, I know you teach Spanish and you lived in Spain for a little bit- are you inspired by that culture at all?

GM: I could talk for hours about every body of work; it’s almost excessive. There’s a quick thing where I relate two experiences in Spain directly. One was living in Cordoba, Spain; they had this tile work, these beautiful patterns. They’re not depicting anything, they’re just patterns describing the beauty of god and nature. Looking at that was different for me because I come from the western tradition where depictions of things are very prominent either in the religious iconography or the commercial iconography. So, that was really wonderful. Then there was also being in the subway in Madrid. You would stand in this curved, dome tunnel and on the side walls they would have the advertisements like they would in New York. The difference was at the time they were using printers that were made for billboards that should be seen at a distance. The pixels were very enlarged, whereas with printing, the pixels should be smaller if you’re looking from a small distance. So if you looked from across the station, you could see them perfectly, but if you stood right next to them they just disintegrated into these patterns made of light and color. I was really amazed in the ways that those things came together to form information, a message, content, images and things like that. It happens again and again in our culture. Morse code was created by Samuel Morse, an artist who lost his wife because she couldn’t receive information in time. He worked with an engineer and they created this system where you divide language by dots and dashes. When you put those together, you get messages. It’s incredible how these multiples developed into a whole depending on the certain code that you’re using. I was really interested in how visual language worked, from computer graphics, to bronze casting to traditional life painting and color theory. My imagery went from figurative to more and more abstract, from objective to non-objective. How do you communicate information? If you want to be a great artist you have to be able to evoke at so many levels. That question just became an interest in itself, what it takes to make meaning.

“I was really interested in how visual language worked, from computer graphics, to bronze casting to traditional life painting and color theory. My imagery went from figurative to more and more abstract, from objective to non-objective. How do you communicate information? If you want to be a great artist you have to be able to evoke at so many levels.”

SM: One last question for you. Has there been any experience or event on this trip that has inspired you the most or made you feel something you hadn’t before?

GM: I feel like every day there has been something incredible to hold on too. Just that pilgrimage to the Lightning Field and seeing that life happening around it. In some ways, the Lightning Field was almost as special to me as finding those prehistoric animals living in a mud pond at the base of it. That really reminded me of how that’s always been something in my life that’s been incredibly important, being able to share with the people around me the beauty and the strangeness of not only the poles in this field, but the creatures that are living there.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Working increasingly in the vernacular of abstraction, Geoffrey Owen Miller works in varying materials, including oil, watercolor, wood, and plaster. Works are project-based and take shape depending on the necessities of each idea's ideal form.

Originally published on Promote & Preserve.